Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy

Volume 54:3 July 2020

Évoluer vers les principes régulateurs au moyen de la

thérapie du jeu synergique

Johanna Simmons

West Vancouver, British Columbia

Abstract

Children generally do not possess the complex, expressive language skills needed to

communicate the struggles they are experiencing. In response to this, a variety of

play therapy models have emerged. This article concentrates on the application of

a research-informed model of play therapy delivery called synergetic play therapy

(SPT), which combines interpersonal neurobiology, attachment theory, nervous

system regulatory principles, mindfulness, physics, and the self of the therapist. By

combining this model with child-centred play therapy (CCPT), the author draws

on two case study examples to demonstrate the efficacy of the SPT model when it is

coupled with CCPT. The findings and case studies suggest that this approach reduces

the severity of identified behavioural concerns. Future investigations in this area are

recommended given the gap in the literature regarding combining SPT and CCPT.

Résumé

En règle générale, les enfants ne possèdent pas les compétences linguistiques

complexes et expressives qu’il faut pour communiquer les luttes intérieures qu’ils

éprouvent. C’est pour combler cette lacune que divers modèles de thérapie par le jeu

ont vu le jour. Le présent article est centré sur l’application d’un modèle inspiré par

la recherche portant sur la prestation d’une thérapie par le jeu et appelée thérapie par

le jeu synergique (TJS), qui conjugue des éléments de neurobiologie interpersonnelle,

de la théorie de l’attachement, des principes régulateurs du système nerveux, de la

pleine conscience et du Soi du thérapeute. En associant ce modèle à la thérapie par le

jeu centrée sur l’enfant (TJCE), l’auteure s’inspire de deux exemples de cas à l’étude

pour démontrer l’efficacité du modèle TJS utilisé en conjonction avec la TJCE. Les

résultats et les études de cas semblent indiquer que cette approche réduit la gravité

des problématiques comportementales décelées. On recommande d’effectuer de plus

amples analyses dans ce domaine étant donné la pénurie de données sur la combinaison

de la TJS et de la TJCE.

Play is the way children express their inner world. According to Landreth

(2012), a pioneer in the field, “Play is the language of the child and toys are their

words.” It is a key part of healthy child development. Further, as play researcher

Marshall (2012) noted,

Research about play highlights its role in supporting cognitive, social-emotional,

and physical development. Play is also seen to strengthen creativity and

academic achievement, and relieves the symptoms of attention deficit disorder,

anxiety, depression, and other potentially debilitating health conditions like

obesity and diabetes, among its numerous major health benefits. (p. 3)

According to Brown (University of Minnesota, Center for Spirituality and Healing,

2011), not only will play improve physical and emotional well-being, but

also, its neurobiological effects optimize the learning process.

Taking a closer look at the types of play children engage in, it is important to

be aware of six primary developmental play stages identified by Mildred Parten

(as cited in Geismar-Ryan, 2012) through observation: solitary play, onlooker

play, parallel play, associative play, co-operative play, and games with rules. In

turn, these six levels appear to correspond with both children’s developmental

growth continuum and chronological age. Solitary play appears typically from

birth to 2 years of age, parallel play from 2.5 to 3.5 years of age, associative play

from 3 to 4.5 years of age, co-operative play from 4 to 4.5 years of age, games

with rules from 6 years on, and onlooker play at all ages (York Region Preschool

Speech and Language Program, 2014).

This is significant because the stage of play that children engage in initially

can be a further indication of their developmental age. As therapy progresses,

we can expect to see the child’s type of play change and move toward matching

their developmental age.

Play Therapy Defined

According to the American Association for Play Therapy (n.d.), this form of

therapy intervention is defined as “the systematic use of a theoretical model to

establish an interpersonal process wherein trained Play Therapists use the therapeutic

powers of play to help clients prevent or resolve psychosocial difficulties

and achieve optimal growth and development.” Since children communicate their

wants, needs, and feelings largely through play behaviours, play therapy becomes

the natural pathway for a child’s communication system and the primary vehicle

through which the child is able to express an understanding of their world.

The primary reason for play to be viewed as the major communication system

of children is due largely to the limitations of their brain function. Children’s

brains are underdeveloped so that the part of the brain responsible for understanding

and articulating with any accuracy what is being felt has not matured. These

executive functions require the prefrontal cortex, which in the case of a young

child is in its infancy of development.

As Ludy-Dobson and Perry (2010) described in their extensive research, brain

development begins with the most primitive part of the brain, the brain stem,

which is responsible for survival functions (e.g., arousal states, controlling key

body functions, heartbeat, swallowing, and breathing). This is followed by the

emergence of the diencephalon, the part of the brain that guides sensory functions,

after which limbic activity emerges where important tasks of the developing

brain integrate further, which helps to manage arousal states such as fear, stress,

and sleep patterns. Thus, the groundwork has been laid for the emergence of the

higher order cognitive functions of thinking, sequencing, problem-solving, planning,

organizing, and all the responsibilities associated with abstract thinking as

well as the process of social-emotional integration.

According to Siegel (2014), all of this is preparatory to higher order thinking

and processing, which does not appear to mature fully until people reach the ages

of 25 to 28 years. Furthermore, Siegel and Bryson’s (2011) research supports the

theory that children are essentially right brain dominant and that play is considered

a right brain dominant activity.

Because a child’s cognitive brain is so underdeveloped, talk therapy is ineffective.

Play therapy does not require a high level of communication. Play therapy

allows therapists to communicate to a child through the world that they have

created. Furthermore, a child can recreate their world in play and in the play

therapy session. Whatever the child presents can be seen as a metaphor for

the child’s own experience(s). A play therapist then works to stay in the child’s

metaphor, reflecting its content and the feelings associated with the metaphor.

Through the play, children are able to confront their own issues safely because the

play distances them from having to unpack the more literal content. In general,

children are inclined to move toward positive health (Landreth, 2012) and the

play allows for working with the psychological material at a safe distance and in

a safe way, guided by and witnessed by the play therapist.

If the child enters the play therapy process with some indication of trauma

exposure, the play behaviours of the child will provide important information

about the child’s age when the traumatic events were experienced. This is because

brain development becomes arrested at the site of the developing portion when

the event(s) occur (Ludy-Dobson & Perry, 2010). Through play, the therapist is

able to meet the child at their developmental age, which may not be the child’s

chronological age. It then becomes possible to observe and to bear witness to the

child’s play behaviours in order to assess a true developmental age over time. We

can possibly draw the conclusion that the same holds true for the types of play.

The type of play that a child engages in becomes arrested at the age a traumatic

event occurred as well.

Child-Centred Play Therapy

Both Axline (1969) and Landreth (2012) hold the belief that children know

what they need to move toward growth and change. CCPT allows children to

orchestrate the direction and the pace of therapy. One of the most commonly

practised approaches is CCPT. It is an evidence-based approach (Ray, 2006) that is

referred to commonly as non-directive play therapy. The therapist tracks, reflects,

and creates an ongoing safe environment in which the child can proceed to do

the work needed to move toward repair and healing. This is all provided within

the context of unconditional regard and full acceptance of who the child is, all

primary tenets of play therapy practice.

CCPT, one of the many play therapy approaches, was created by Axline

(1969) in 1947, based on the teachings of Rogers (1995), who believed that

the therapist’s genuineness or congruence, unconditional positive regard, and

empathic understanding create the foundation for this work to take place. These

three conditions, Rogers wrote, are essential for growth. He stated that the more

therapists are themselves, the greater the likelihood of change. Rogers wrote that

therapists must be congruent in what is experienced at the “gut level” (p. 116)

and in what is expressed to the client. Unconditional positive regard means that

the therapist accepts the client however and with whatever they present. Empathic

understanding means that the therapist senses the feelings and meaning of the

client’s experience accurately.

Regulation

To enter a regulated state, Dion (2018) wrote that one would need to display

many of the following: the ability to think clearly and logically, to make eye contact,

to display a wide range of emotional expression, to take full breaths, to feel

grounded, to communicate in a clear manner, and to have an internal awareness

of both body and mind.

For this study to have an appropriate context, it is important to acknowledge

the role that the concept of regulation plays in identifying and assessing ongoing

growth and competence in children. Increasingly, researchers and practitioners

alike are exploring the importance of brain science and the factors that impact

and determine what will benefit children’s brain structures most and what will

enable children to know and to be able to access their own internal resources.

Badenoch (2008) wrote that interacting with a safe, accepting person has the

capacity to change a child’s brain structure, thereby providing the child with more

internal accessible resources. Furthermore, in the process of being in the presence

of a safe, accepting person, the child gains the capacity to use that person, in this

case the therapist, to regulate toward a state of calm (Badenoch, 2008). Referred

to as co-regulation, this is seen best in the early development of infant to mother

attachment, whereby the mother soothes the crying infant through a variety of

co-regulating activities such as rocking, swinging, and cooing.

Badenoch observed further, “We don’t come with any kind of regulatory

circuitry but it has to be co-built with another person” (Badenoch, 2017, 3:48).

In other words, we learn to regulate by experiencing co-regulation first. SPT

acknowledges that children use their mothers for regulation before children

can regulate on their own and that children’s work with therapists as their coregulators

is an important tenet of SPT (Dion, 2008).

In terms of typical developmental growth, mothers function as the initial

“external regulators” (Dion 2018, p. 52) for their children. In play therapy, the

therapist works to become the external regulator for child clients. For co-regulation

to evolve fully, something that can lead to self-regulation, the development

of the cortex and its integration with the limbic system must develop and mature

first. Drawing on the research of Iacoboni (as cited in Badenoch, 2008, p. 37),

“Mirror neurons are circuits of the brain that are used to internalize the intentional

and feeling states of those with whom we are engaged.” Badenoch (2008) added

that self-regulation involves the cortex, which is in its infancy of development. For

this reason, co-regulation must occur in order to begin creating the integration

of the limbic region and the cortex needed for self-regulation.

The intention underlying the therapy delivery process for the two young

children in this study is to examine play therapy effectiveness overall and the

ways in which the work can be enhanced in terms of its effectiveness. The data

provided represent a small sampling of how combining traditional play therapy

models, specifically CCPT with SPT, can impact social and emotional growth

and lead to several positive outcomes. As previously indicated, research directed

at the question of optimal play therapy interventions suggests anywhere from 30

to 40 full sessions to achieve optimal play therapy treatment effect (Lin & Bratton,

n.d.). This study was designed to reflect fewer sessions overall with possibly

greater intensity delivered throughout each child’s therapy process.

Synergetic Play Therapy

Dion (2008), the creator of SPT, identified what she believed were nine

specific tenets to the process of SPT. Strongly influenced by CCPT, experiential

play therapy, and Gestalt play therapy, the tenets are condensed and summarized

best as follows:

• the attunement between therapist and child,

• the modelling of self-regulation by the therapist,

• the authenticity and the congruence expressed by the therapist,

• the symptoms expressed by the child as the dysregulated states of the

nervous system,

• the focus placed on a child being who they are genuinely, rather than

functioning as perceived expectations

• the understanding that children project aspects of their inner world onto

toys and other play objects,

• the understanding that children also project their inner world ideas and

beliefs onto the therapist, and that, in so doing,

• the therapist comes to feel and have the experience of what it is like to be

the child client.

Genuine emotional response will be evoked in the therapist who is attuned to

the child emotionally, as the child will project their emotions onto the therapist

(Dion, 2018). It is important that therapists practising SPT model regulation as

they flow through the “crescendos and decrescendos” (Schore, 2006, as cited in

Dion & Gray, 2014, p. 59) of their own internal states. These referenced internal

states are like the “crescendos and decrescendos” of a child’s arousal system

(Schore, 2006, as cited in Dion & Gray, 2014, p. 59).

In modelling regulation, the therapist activates the child’s own mirror neuron

system. This, in turn, can initiate new neural firing patterns in the child, thereby

replacing negative emotions associated with memories (Badenoch, 2008; Siegel,

1999). Throughout this process, as highlighted by SPT, a therapist strives to work

at the edge of what is termed a “window of tolerance.” This is identified as a place

bordering on the discomfort of their feelings without losing control, somewhere

between a regulated state and a dysregulated state. The goal here is to expand

mutual windows of tolerance, the child’s and the therapist’s (Dion & Gray, 2014).

What distinguishes Dion’s SPT approach from Landreth’s CCPT model is that

the Dion’s approach encourages a therapist to express congruent feelings in the

play therapy process, whereas Landreth (2012) argued that the therapist’s statements

during sessions may interfere over time with maintaining the child as the

primary focus of the therapy experience. This raises the question of which belief

system promotes change the most effectively.

To respond to this question, the author of this study has chosen to draw upon

SPT, an adjunctive approach, to support the work of CCPT, generally a standalone

model, in order to assess the benefits of this combined approach. This study

will demonstrate that these children moved toward wellness efficiently and more

quickly than with CCPT alone. According to Leblanc and Ritchie and to Bratton

et al., the optimal play therapy treatment effect falls within 30 to 40 sessions

(Leblanc & Ritchie, 2001; Bratton et al., 2005, as cited in Lin & Bratton, n.d.).

Purpose of the Study

Drawing on data gathered through examining the play therapy processes of

two male children of preschool age, the author was interested in exploring the

efficacy of a combined therapeutic model. The overarching goals in the two cases

were the ability to make gains in observable self-regulatory behaviours and to

increase a sense of self-awareness and personal identity. As a result of a combination

of non-directive play therapy model and SPT principles, it should be possible

to maintain and promote developmental growth stages in the play behaviours

expressed by each child, to enable each child to gain personal understanding and

appreciation for the transitions being expressed through their play behaviours,

and to learn to draw upon the gains made through increased play behaviour

transitions to multiple settings (e.g., home, preschool, social settings, and possibly

recreational activities).

Method

Using a qualitative case study approach, the therapist sought to explore the

efficacy of applying combined play therapy approaches: CCPT with SPT principles.

The therapist gathered quantitative data from a pre- and post-therapy

checklist that had been designed by her. The checklist was completed by the

parents. The therapist’s case notes and the parents’ anecdotal reports were also

taken into consideration for the purpose of this study. This approach allowed

the research to focus on a particular phenomenon, to provide rich description,

and to offer a different understanding of the core relationship and interactions

between child clients and their therapist (Merriam, 1991). Both children worked

with the same therapist.

The therapist met with the parents briefly after each session, letting the parents

know how they could continue building the regulation skills that had been

modelled in session. Parents also presented challenges they had faced at home in

order for the therapist to provide support within the framework of the therapeutic

model. Psychoeducation regarding brain development, the states of the nervous

system (hyperarousal, regulation, and hypoarousal), as well as different activities

to help with regulation were also provided to the parents.

Study Participants

Under the pseudonyms of “John” and “Tom,” two boys of similar preschool

age were identified for this study. John had a chronological age of 4 years and

11 months at the onset of this study while Tom had a chronological age of 4

years and 9 months. Both children were identified as struggling with aggressive

behaviours and with difficulty managing their emotional range. Sensory processing

issues were also present in each child’s overall behavioural presentation. Each

of the boys came from a two-parent family system, and both sets of parents had

identified that their sons were struggling at home and in their preschool settings

equally. In Tom’s case, he was diagnosed formally as being on the spectrum of

autism along with a high level of functioning overall.

Participant 1: John

John was attending his final year of preschool when he was referred for treatment.

The single male offspring in his family system, he lives with his twin

sister, his younger sister (1 year and 7 months old), his mother, and his father.

His parents referred John for play therapy because of his struggles in managing

his emotions and because of his aggressive behaviour at school and at home. As

well, the family’s pediatrician had diagnosed this child previously with an anxiety

disorder, a label the parents tended to question. There were, however, indications

that John had sensory processing issues, according to both parents. John’s mother,

a homemaker, and his father, a professional working outside of the home, were

both actively involved in raising their son.

Both parents expressed their concerns over John’s behaviour pattern when

they or other adults attempted to set limits with him. Biting, scratching, kicking,

spitting, and hitting seemed to occur regularly and made their son seem fairly

volatile. In terms of family interactions, John appeared to get along reasonably

well with his twin sister, but he became angry and aggressive in the presence of

his younger sister, particularly when she sought their mother’s attention. Change,

in the form of transitions, generally caused upset for John, who was identified

as a sensitive child and who indicated, through his behaviours, that he disliked

physical touch. According to the parents, John had had a difficult early birth

history having been born three weeks prematurely, unable to breathe initially on

his own, and needing to be intubated.

The primary direction of the therapeutic intervention for John, in consultation

with his parents, was to work to reduce aggressiveness and to create ways in

which he could learn some strategies to manage his times of dysregulation (“big

emotions” that had got out of control). To this end, John participated in 21

regular play therapy sessions of 1 hour each, with 2-week interruptions in services

for the winter holidays and for spring break. Particularly noteworthy were the

observable changes that emerged in sessions 6, 9, 16, and 21. Progress reports and

ongoing suggestions were provided by John’s therapist, and the parents engaged

in a similar process of feedback to assess gains and the areas where continued

growth was required.

Participant 2: Tom

Tom previously had been diagnosed as being on the spectrum of autism. He

appeared to be functioning at the higher end of the spectrum, with cognitive

capabilities well beyond his chronological age. As well, Tom had a number of

sensory sensitivities that included sound, his sense of smell, and his sense of taste.

Among his capabilities is his facility with languages, as he speaks and understands

both Cantonese and English. At the time of this study, Tom was also involved with

a behavioural interventionist who worked one-on-one with Tom to support him

in attaining goals set out by his school. He is a single child in his family with his

mother, a homemaker, and his father, who works as a professional. Both parents

are actively engaged in their son’s rearing process.

Concerns raised by Tom’s parents focused on Tom’s tendency to get angered

easily, to become very emotional, to shout, to throw things, to run away, to

find difficulty in connecting with his peers, and to have difficulty initiating play

with other children. Added to the list was his tendency to “script,” which his

behavioural interventionist felt impeded his progress. The Autism Society of

Baltimore-Chesapeake (2020) described scripting as “the repetition of words,

phrases, intonation, or sounds of the speech of others, sometimes taken from

movies, but also sometimes taken from other sources such as favorite books

or something someone else has said.” While Tom’s behavioural interventionist

believed the scripting behaviour impacted Tom’s overall presentation in negative

ways, Dion (personal communication, September 30, 2017) maintained that all

children’s behaviour represents their attempt to regulate. In this way, Tom could

be seen as engaging in a purposeful, intentional act.

The goals the parents identified for Tom’s therapy process involved primarily

developing self-regulation capabilities, learning to understand and to appreciate

empathy, and becoming more prosocial with his peers. As with John, Tom’s parents

were apprised of their son’s progress on a weekly basis and observations by

parents and by the therapist were exchanged regularly. Tom participated for a total

of 13 weekly 1-hour sessions with a 6-week break during the winter months to

accommodate extended family travel. For this child, significant shifts in behaviour

began to be seen and were recorded following his seventh session.

Instrument

A questionnaire was used in conjunction with case notes, clinical observations,

and parental feedback. The questionnaire was developed by the therapist of the

study (Simmons, 2015). This instrument was comprised of 30 different but

commonly identified childhood behaviours. They ranged from subject-positive

descriptors that were recorded as added values (e.g., accepts limits, co-operative)

to negative behaviours with lesser values (e.g., displays aggression, fights authority

figures). With this tool, it has been more possible to quantify gains being made in

goal-specific areas such as self-regulation. Data from a 10-point scale with values

of 1 to 10 were collected and compiled to assess the efficacy of the therapies being

applied. Highlighting emotional development gains in the two therapy cases identified,

this study examined the differences from baseline measures, using play as

the intervening variable to assess growth and change in these two children before

and after play therapy intervention.

Procedure

As each case study subject participated for a different length of time, the use

of the study questionnaire was applied at different intervals. For John’s parents,

the first measurement, following the establishment of a baseline, was at session

8. For Tom’s parents, the first measure was done at Session 1.

Data Analysis

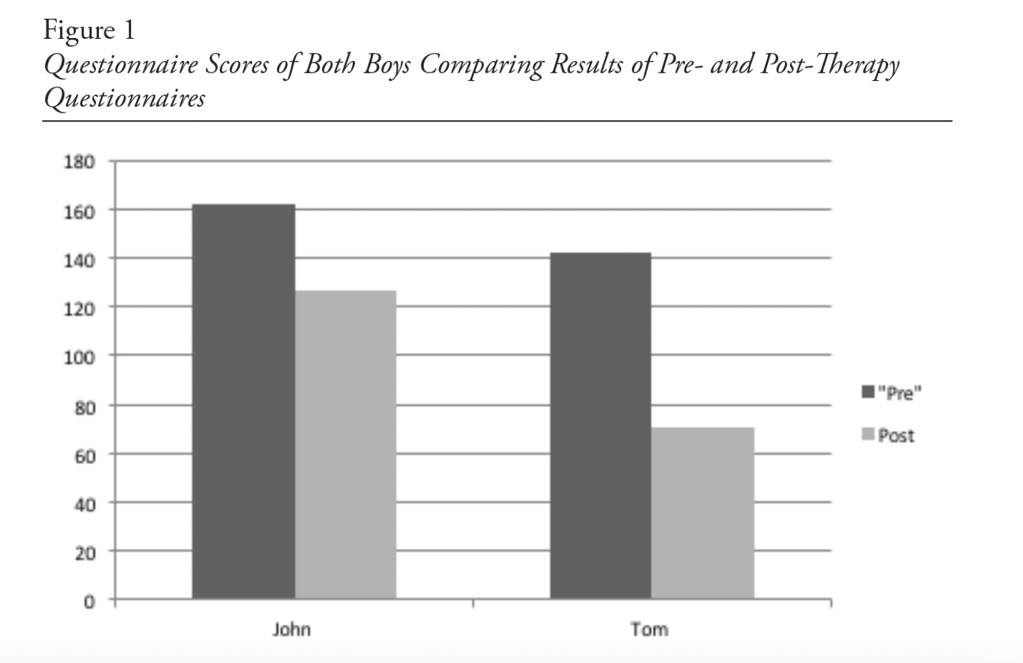

Each questionnaire was tallied to attain a global score (see Figure 1). Scores

from each specified question were totalled and the pre- and post-questionnaire

figures were compared for each subject from their initial questionnaire results to

their second set of measurements. The attained scores were also compared across

the two children’s total scores achieved as they fell into the same cohort from a

developmental perspective. Attained scores, along with case note information

and parental feedback, did provide to some degree a measure of emotional/social

growth and progress made from their respective time and applied interventions

in therapy.

Results

Overall, the results suggest that both children made gains toward less aggression,

more prosocial behaviour, and better management of their regulatory

processes in terms of emotional growth, self-awareness, and more contained transitioning

behaviour. In each family’s case, the improvement overall was maintained

at follow-up a year later. For both families, the challenge of transitioning into

kindergarten was met with success, suggesting that the newer learning evidenced

in the two children’s behaviour was sustained.

John: A Clinical Review of the Therapy Process

Early themes in John’s work suggested feelings of overwhelmingness, chaos, and

entrapment, while ways of responding were limited initially to bouts of aggression.

In his first few sessions, he tended to engage primarily in solitary play, and his

behaviours expressed deep feelings and bodily sensations arising from these feelings.

These were tracked by the therapist and efforts were made to support these

deep-seated expressions. As John displayed his overwhelmingness and chaos in

his play, the therapist noticed her breath quickening and a tightness in her chest.

As per the SPT model, the therapist expressed these sensations then regulated

through these sensations while verbalizing how she was regulating.

Drawing on psychodynamic theory, the therapist identified a self-object

dynamic around session 5 that seemed to replicate the child’s own early life

experience, which was, in turn, replicated through the play. In this dynamic, the

therapist was able to feel the same sense of helplessness and need that the client

had felt. Feelings of being trapped, of choking, of having to fight for survival were

expressed and played out and could be expressed by the therapist as authentic

feelings shared by client and therapist alike.

Session 6 was a pivotal one in which John projected an experience of being

trapped and unable to move during play. When the therapist tried to regulate

through the discomfort, John told her not to move or to breathe. As John was

pretending to put things into the therapist’s mouth, she noticed an uncontrollable

urge to move and to pull things out of her mouth. It was then that the therapist

learned that John had been intubated at birth and had removed his tube himself,

a big feat for a newborn.

The theme of choking, of having one’s breath taken away, was played out in

session nine as well, with the therapist verbalizing and modelling co-regulating

patterns such as deep breathing and ways of grounding. John played with his

self-object where he put the object in water and said that the self-object could not

breathe. The therapist noticed a tightness in her chest, which Dion (2018) stated

is a projective experience, the child projecting their feelings onto the therapist

so that the therapist can experience what the child is feeling. The therapist then

regulated through this discomfort, after which John removed the object from the

water and went to another area to play.

Later sessions were distinctive in that he chose to bring in his own toys and to

engage with the therapist in co-operative and associative play, both developmentally

closer to John’s chronological age. Having interacted with his play therapist

and witnessed her as the “external regulator” (Dion, 2018, p. 52)—talking,

breathing, acknowledging what she was experiencing, and changing physical

positions—John was now mirroring the therapist’s breath and movement.

In John’s last few sessions, much of his work expressed a state of regulation, and

he was able to demonstrate ways to regain his regulated state. At this same time,

John’s mother reported that he was now using his words to describe what was

causing his dysregulation at preschool. He was also playing more co-operatively

with his twin sister. Previously their play had been parallel play and John would

get upset if she tried to engage him in play.

As the progression of John’s play continued, the play itself continued to evolve.

He had begun his play therapy process as though a very young child, engaged in

parallel play and solitary play exclusively, with very little dialogue, often using

guttural sounds instead of words, and ended his process engaging with the therapist

in a co-operative form of play usually associated with children ranging in

age from 4 to 5.5 years. His journey had helped him develop as a child whose

emotional age and chronological age were now matched, which was one indication

that the therapy process was nearing the end. Child-centred play therapists

and synergetic play therapists hold the belief that the child knows what is needed

to heal what has been harmed.

The final session for John appears to reflect this belief system. On entering the

play therapy space, he elected to choose a board game to play with the therapist

and later proceeded to revisit each of the toys or activities that had activated his

dysregulation in earlier sessions. In each case, he was able to process what he

had gained from interacting with each particular play experience and to close off

his connection with it. A final activity that John chose to play out was when he

selected his self-object, a toy lizard, and had his therapist hold it while he created

a healing act on it, assuring his therapist that the toy was now all better.

In the year that has passed, John has managed to adapt to his kindergarten

program successfully. He has had a good year and looks forward now to his grade

1 year. The process began then moved from assessment and relationship building

to a working phase and then to closure, all in a total of 23 sessions with the bulk

of the significant and measurable shifts occurring in sessions 14 onward.

Tom: A Clinical Review of the Therapy Process

Tom tended to choose the same form of play in most of his early sessions, playing

with Brio trains, building tracks to curve and travel upward and downward

while the therapist’s job was to create some tunnels. The developmental stages of

the play were a combination of solitary and parallel play. During this play, Tom

appeared to be regulated and engaged. In those times when he became dysregulated,

he was seen to be scripting, which suggested that he used this behaviour in

an attempt to achieve some measure of regulation for himself. As his play therapy

progressed, there appeared to be less scripting behaviour, which he replaced more

frequently with calming breaths.

The therapist noticed some visceral impact from the movements of the train. As

the toy moved steadily along the tracks, it was possible to use non-verbal tracking

to follow its course. But when the train travelled up and down the hills that had

been created, the therapist became aware of her own bodily sensations: tension

building in her chest followed by a big release of this tension as the train moved

quickly down the other side of the created train route. This visceral experience

was then communicated verbally to the client in a step-by-step fashion. Speaking

of the sensation of having had to hold breath and then releasing it was replicating

Schore’s discussion of “crescendos and decrescendos” (Schore, 2006, as cited in

Dion & Gray, 2014, p. 59) experienced in the autonomic nervous system. In this,

the therapist was serving as the child’s “external regulator” (Dion, 2018, p. 52). In

the early sessions, the transitioning that followed demonstrated that Tom found

it hard to complete the play and to leave the play therapy space.

By session 7, Tom had begun to be more exploratory in his play and to vary

his choice of play objects and where he moved in the room. Changing the order

of his choices, he started to use the sand tray before engaging with the trains. A

second observable shift occurred when he started to verbalize at a specific point

in the train travelling sequence using the term “biacalee,” a word drawn from

his imagination. A new pattern then emerged in which Tom would shift his eye

gaze to the therapist, and then, just before the train entered the tunnel, mirroring

both the gaze and reflecting the word, the therapist would say “biacalee” in

tandem with the child. The therapist expressed aloud that she noticed Tom’s

intention, through his eye contact, to have her join him in this expression and

timing. Coinciding with this event, Tom appeared better able to transition out

of the play therapy space.

In a subsequent session, the same pattern was seen, and in follow-up, the

therapist learned from Tom’s father that before Tom became upset, he would take

a breath, and that this new behaviour was being seen at home with some consistency.

Further, when the father reflected to his son that he noticed the breathing,

Tom told his father that “I’m breathing like Johanna [the therapist] taught me

to.” This coping tool was never directly taught; rather, it was modelled by the

therapist, who served as the child’s “external regulator” (Dion, 2018, p. 52) during

play therapy sessions. Following this, therapy was put on hold as the family

was away for six consecutive weeks. When they returned, Tom had continued to

maintain the eye contact seen in his previous work, and after several more play

therapy sessions, it was felt that his process could begin to wind down.

The family continued to report their son’s progress. The father told the therapist

that his son had transitioned back to his preschool class without incident and

that within two more weeks Tom was working co-operatively with a schoolmate.

In a following session, Tom presented the therapist with a train so that her train

could follow his own. The play level by this time had achieved the co-operative

level of development. In consultation with the parents, it was agreed that session

13 would be his final one because Tom was displaying observable progress across

several areas the parents had identified originally. Key gains were Tom’s ability to

regulate his anger, to engage in co-operative play, and to make eye contact effectively.

These improvements suggested that Tom’s developmental and chronological

age were now more congruent.

Discussion

While there are numerous methods for engaging in play therapy practice,

the use of the therapist as discussed in this study is both distinctive and to some

degree controversial. The methodology draws on both historical teachings in the

field as well as on newer approaches that are informed strongly by neuroscience.

Children’s understanding and generalized perception of their immediate world

contains the influences of parents, school, neighbours, friends, and others. This

understanding and perception is reflected in the stages of play activity. Growth

was evident and measurable in these case studies. In each case, the identified child

was able to communicate through his behaviours and the emotions associated

with these behaviours that there was struggle, pain, and an inability to engage

fully with his world in a successful and maturational fashion. As an exploratory

study, the role of the parents was also an important consideration.

Parents, taught to be key observers who can reflect their child’s witnessed

behaviours and emotions, expand the reach of play therapy effectiveness. In the

two case studies described, therapist and parents needed to partner in order to

track the effects of the sessions and the carry-over managed by the family between

sessions.

Limitations and Conclusion

The small sample size for this study was both an advantage and a disadvantage

in terms of the ability to focus on the key elements of working with combined

play therapy approaches. It would be of value to be able to expand the sample

size to demonstrate further the efficacy of SPT principles with foundational

CCPT. Being able to explore these two methodologies with greater cultural variation

would also help to increase understanding about the degree of emotional

expression typical across ethnic groups, about the role parents play in impacting

play behaviours with their children, and about the role “play” actually has in the

overall development process of these children.

Further, a comparative look at sampling children who received a single play

therapy approach (e.g., CCPT) on its own versus a group who receive the combined

approach would enhance our understanding of the efficacy of this combined

approach. In addition, replicating these results with other therapists and clients

would lend more weight to the findings of this study.

Communication to parents cannot be controlled between therapists or how

parents are supporting or not supporting the process at home. These are factors

that can have bearing on the results when replicating this study. Asking not only

parents but also teachers and other adults in contact with a child to complete the

behaviour assessment would be worth considering for future studies. It is also possible

that some of the growth of the child, as noted in the progression through the

play stages, is a result of the child becoming more comfortable with the therapist.

The child’s maturation over the span of therapy may have contributed also to a

portion of the growth. Further studies would benefit from using control groups

to control for these elements.

The results indicate that in both cases described in this study, the children’s

negative behaviours decreased: Tom’s by 50% and John’s by 30%. These changes

occurred well below the 30 to 40 sessions suggested by Lin and Bratton (n.d.).

In addition, the findings of this study demonstrate that the addition of SPT—

allowing for genuine, authentic expression by the therapist of the impact of the

play itself and the role of the therapist as “external regulator” (Dion 2018, p. 52)

of the child’s range of emotions—appears to assist the child actively in learning

how to self-regulate.

Therefore, the addition of the synergetic process to the child-centred process

enhanced the learning that occurred and enabled John and Tom to become their

own internal regulators. Once this occurred, there was no longer a need for the

children to express distress through aggression or through any other maladaptive

behaviour. Regulation becomes the primary goal for therapy. Dion (2018) stated

that symptoms and behaviours are viewed as dysregulated states of the nervous

system. The play for each child transitioned from that of a very young child to a

stage in which each boy was able to engage in an age-appropriate fashion across

different settings and circumstances.

The three goals, as set out in the purpose of the study, have been met. The

children have been able to maintain emotional development as reported by the

parents one year after the termination of play therapy. The therapist observed the

changes in the children’s behaviour as expressed through the play by the gains

expressed in the pre- and post-assessments as well as through anecdotal reports of

the parents. The preschool teachers as well as support staff expressed the progress

that they had noted in the children’s behaviour and an overall improvement in

social behaviour to the parents.

References

Association for Play Therapy. (n.d.). Clarifying the use of play therapy. https://www.a4pt.org/

page/ClarifyingUseofPT

Autism Society of Baltimore-Chesapeake. (2020). Scripting. https://www.baltimoreautismsociety.

org/glossary/term/scripting/

Axline, V. M. (1969). Play therapy. Ballantine Books.

Badenoch, B. (2008). Being a brain-wise therapist: A practical guide to interpersonal neurobiology.

W. W. Norton and Company.

Badenoch, B. (2017). The myth of self-regulation [Webinar]. Sounds True. https://www.soundstrue.

com/store/leading-edge-of-psychotherapy/free-masterclass-video1?sq=1

Dion, L. (2008). Philosophy of synergetic play therapy. Synergetic Play Therapy Institute. https://

synergeticplaytherapy.com/philosophy/

Dion, L. (2018). Aggression in play therapy: A neurobiological approach for integrating intensity.

W. W. Norton and Company.

Dion, L., & Gray, K. (2014). Impact of therapist authentic expression on emotional tolerance

in synergetic play therapy. International Journal of Play Therapy, 23(1), 55–67. https://doi.

org/10.1037/a0035495

Geismar-Ryan, L. (2012). Infant social activity: The discovery of peer play. Childhood Education,

63(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.1986.10520766

Landreth, G. L. (2012). Play therapy: The art of the relationship. Routledge. https://doi.

org/10.4324/9780203835159

Lin, Y.-W., & Bratton, S. C. (n.d.). Summary of play therapy meta-analyses findings. Evidence-

Based Child Therapy. http://evidencebasedchildtherapy.com/meta-analysesreviews/

Ludy-Dobson, C. R., & Perry, B. D. (2010). The role of healthy relational interactions in

buffering the impact of childhood trauma. In E. Gil (Ed.), Working with children to heal

interpersonal trauma: The power of play (pp. 26–43). Guilford Press.

Marshall, D. (2012, Spring). Playing alone: How unstructured play improves children’s health.

Child Health Talk, 3–4. https://www.nbcdi.org/sites/default/files/resource-files/CHT%20

Spring%202012.pdf

Merriam, S. B. (1991). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. Jossey-Bass.

Ray, D. C. (2006). Evidence-based play therapy. In C. E. Schaefer & H. G. Kaduson (Eds.),

Contemporary play therapy: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 136–157). Guilford Press.

Rogers, C. R. (1995). A way of being. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who

we are. Guilford Press.

Siegel, D. J. (2014). Brainstorm: The power and purpose of the teenage brain. Jeremy P. Tarcher/

Penguin.

Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2011). The whole-brain child: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to

Nurture Your Child’s Developing Mind. Delacorte Press.

Simmons, J. (2015). Self-developed questionnaire [Unpublished manuscript].

University of Minnesota, Center for Spirituality and Healing. (2011, 23 May). Interview with

Dr. Stuart Brown, founder of the National Institute for Play [Video]. YouTube. https://www.

youtube.com/watch?v=C9mEyuZ6Ir8&t=2s

York Region Preschool Speech and Language Program. (2014). Stages of development of social

play [Webinar]. Markham-Stouffville Hospital. https://childdevelopmentprograms.ca/

elearning-modules/the-power-of-play/story_content/external_files/Developmental%20

Milestones%20of%20Social%20Play%20and%20Sharing.pdf